The Spaces They Inhabit: Cinematographer Nils Clauss Talks with Use All Five

Can you tell us why you moved to Seoul and what about the city or culture seduced you to stay?

I remember that personally it felt necessary for me to try out something different. Sometimes you feel if you don’t make that certain decision then you have to deal with regrets later on. I was at a point in my life where I was comfortably able to leave: I just graduated from Humboldt University in Berlin with a degree in Visual Cultures. Instead of looking for work in Germany, I wanted to pursue my passion in photography and also finally pick up a camera to make films rather than only analyzing them theoretically like I did during my previous studies. Of course films can be made anywhere, but I think once you immerse yourself in a very different environment and culture, it sometimes makes it easier for you to open up and follow your dreams. So I was ready for that move. Moving to Korea was mainly triggered by Lee Myung-se’s film “Nowhere to Hide”, which I watched at the Melbourne International Film Festival when I studied abroad in Australia for a year in 2000. It was the first Korean film I watched. Visually and creatively the film blew my mind. Even though I already decided to write my master thesis on Wong Kar-wai, since his films got me interested in cinema in the first place, I was watching a lot of Korean films as I went along. When I was in Hong Kong to do research for my master thesis on Wong Kar-wai’s work, the idea brewed to go and move to Korea after graduation. Now, I have lived here for thirteen years. Last year my film “Plastic Girls” was given the jury award at an international film competition, which was held in Seoul. Lee Myung-se happened to be the head of the jury. When he handed me over the trophy at the award ceremony, suddenly to me it all made sense and it felt like another chapter of my life had been written.

Aside from my personal motivations to be here, I always felt that these have been interesting times to be and work in Korea. Since the end of the Korean war the country has, for better or worse, developed at a tremendous pace. Furthermore, the constitutional revision that officially ended the military rule in South Korea in 1987 is just over 30 years old. So obviously Korea’s democracy is still young and with recent political developments during the Lee Myung-bak and the Park Geun-hye administrations, we also see how much it has been struggling. During those years (2008 – 2017) the society shifted apart mentally and economically more than ever and what was left when president Park was impeached was a much less homogenous Korean society. All this against the backdrop of the country’s historical past, has lead to extreme social developments, but fortunately also caused a very vivid debate in Korean society. Therefore I find it very inspiring to live and work here as a filmmaker and photographer.

When I first moved to Seoul, it still felt like the creative scene was waiting for its coming out. But suddenly everyone started to feel the change. And once there is a change in Korea, everything tends to happen fairly quickly. Some say that having been in Seoul during the late first decade of the 2000s, felt like being in Tokyo in the 1980s when the simmering underground culture suddenly found its space. I remember when I moved from Berlin to Seoul end of 2005, everyone seemed very skeptical about my move to a place no one really had a connection to in the West. Ironically when I went to visit Berlin a couple of years later, suddenly everyone was talking about Korea, everyone was familiar with eating Korean food and Korean art and artists were suddenly promoted internationally. Obviously the creative scene in Seoul has caused a lot of international hype and recognition. But if you look at Korean film for example, I always thought that the 1990s was the best time in Korean cinema. By the time Korea opened up to the Western market and terms like “Korean New Wave” had been shaped, Korean cinema was already on its downfall, since the local industry was struggling to compete with the Hollywood industry. Unfortunately most investors here in Korea became less concerned about the content and merely were concerned about the next big financial success. After all the most interesting times to have lived in Seoul, probably would have been the 1990s, I suppose. But what I still really appreciate about Korea is the fact that things never settle down and get boring. Most parts of Asia in general have a very innovative character, whereas Europe on the other hand can seem very static, I believe.

In your recent Korean culture trilogy you touch on 3 foundational aspects of life – working and living conditions in Bikini Words, dealing with loss in Last Letters, and sexuality and public spaces in Plastic Girls. How do you consider your perspective as an immigrant from a different culture? Does it give you clarity, bias? Does it help you to deconstruct the basic elements and communicate them in the tight format of a short film?

My perspective, as an immigrant, I merely understand as a gift on many levels. On the flip-side it also adds a lot of confusion, since it creates a sort of limbo, where you start to question your own roots, but also have to understand that the adopted country you live in is not set up with a value system, which makes it easy for you to fully be integrated as an immigrant. Korea has been a very homogenous culture to date, so most people seem to find it difficult to understand that some immigrants may want to stay indefinitely. Despite that I felt at some point that in general Koreans are very receptive to cross-cultural viewpoints in regard to their country. For example when Neil Dowling and I made the “Lonely C” music video about 8 years ago, it turned out to be a success equally for an international, but also a Korean audience. For everyone in the West it almost seemed like an entry point of contact with Korea, whereas for Koreans it showed an almost forgotten old-fashioned countrified image. In a way it made the Korean audience feel a bit emotional and sentimental about their own past in a country which very quickly changed from an agricultural state to one of the leading industrial nations. This transition happened so quickly that for most people it was hard to grasp.

But to have a perspective with a certain clarity and bias as an immigrant, I feel it is important to place yourself somewhere in the middle-ground between your own culture and your culture of choice. When I first came to Korea I tried to immerse myself in the culture as much as possible and wanted do everything appropriately in the Korean way in order to not be offensive or stick out. But soon I realized that not only did my adopted environment not provide a structure to fully assimilate myself, but also that a big part of my identity is rooted in a different cultural value system. At both extremes you either have to sacrifice parts of your own identity, or you quickly turn your back against your newly adopted culture. This later dilemma I tend to see among many expats living in Korea. The consequence is a form of culture bashing, which makes it not only difficult for them to assimilate, but also takes away that certain clarity, which I find allows for a more neutral almost observer-like point of view.

This of course raises the question what kind of criticism can you possibly engage yourself in, if you live in a society which is so different from your own and possibly conflicts with your beliefs? Even after living here for 13 years, Korea, in many ways, is still very complex and inscrutable to me. As an expat it sometimes sets you into this hybrid world, where not only do you feel more and more out of touch with your own culture, but also find it difficult to fully make sense of your adopted home. This is where it helps me to work as a filmmaker. Engaging in different facets of culture as a (visual) storyteller helps to bridge an adopted home to something you simply consider home. With that in mind and considering the middle ground described above, which I feel I inherited, I try my best not to be offensive towards South Korean society, but rather create more of a general statement, which illustrates a more global tendency. In this regard “Plastic Girls” is a good example. Rather than saying that gender inequality is an issue only with regard to Korea as a nation, the specific focus on the sexualization of public space, is something a global audience will be able to relate to. It is my intention to create a certain awkwardness without being directly offensive towards anybody or by utilizing national stereotypes. Even though this film is shot in Korea and references various distinct Korean public spaces, I really hope that this film speaks to an international audience and not only makes us look at gender misbalances in Korea, but allows us to reflect on how the culture produces a certain view of women in general and how we think about an ongoing trend regarding a sexualization of public space.

Once you position yourself in the middle ground of a cross-cultural background, you also not only see cultural characteristics, which stick out, but also learn how to interpret and analyze them. That again adds to a perspective with clarity and bias. Whereas the plastic mannequins, which are rooted in the Korean service and acquisition culture, may not stick out as something different, unknown or unique to most Korean passersby, a foreign viewpoint unfamiliar with Korean history and culture will probably struggle to put this phenomena into a cultural context. In order to make sense of the existence of the plastic mannequins, Korean author Kim Yung Chung’s book “Women of Korea: A History of Ancient Times to 1945”, allows us to make a really interesting connection. Based on her text I understand the plastic mannequins within the context of the Korean Kisaeng culture. Kisaengs were female artists who would entertain kings and people of higher status. Whereas they were mainly seen as entertainers engaging in fine arts, poetry and prose, they also were providing sexual services. Kim explains that Kisaeng houses were mostly located close to the center of town around marketplace areas. I find it very interesting that she explains that these places were laid out to create a welcoming effect and that the area around the house would be landscaped with ornamental pools and plants. Therefore I feel that in a way the plastic mannequins in “Plastic Girls” can be see as a modern interpretation of a traditional Korean Kisaeng.

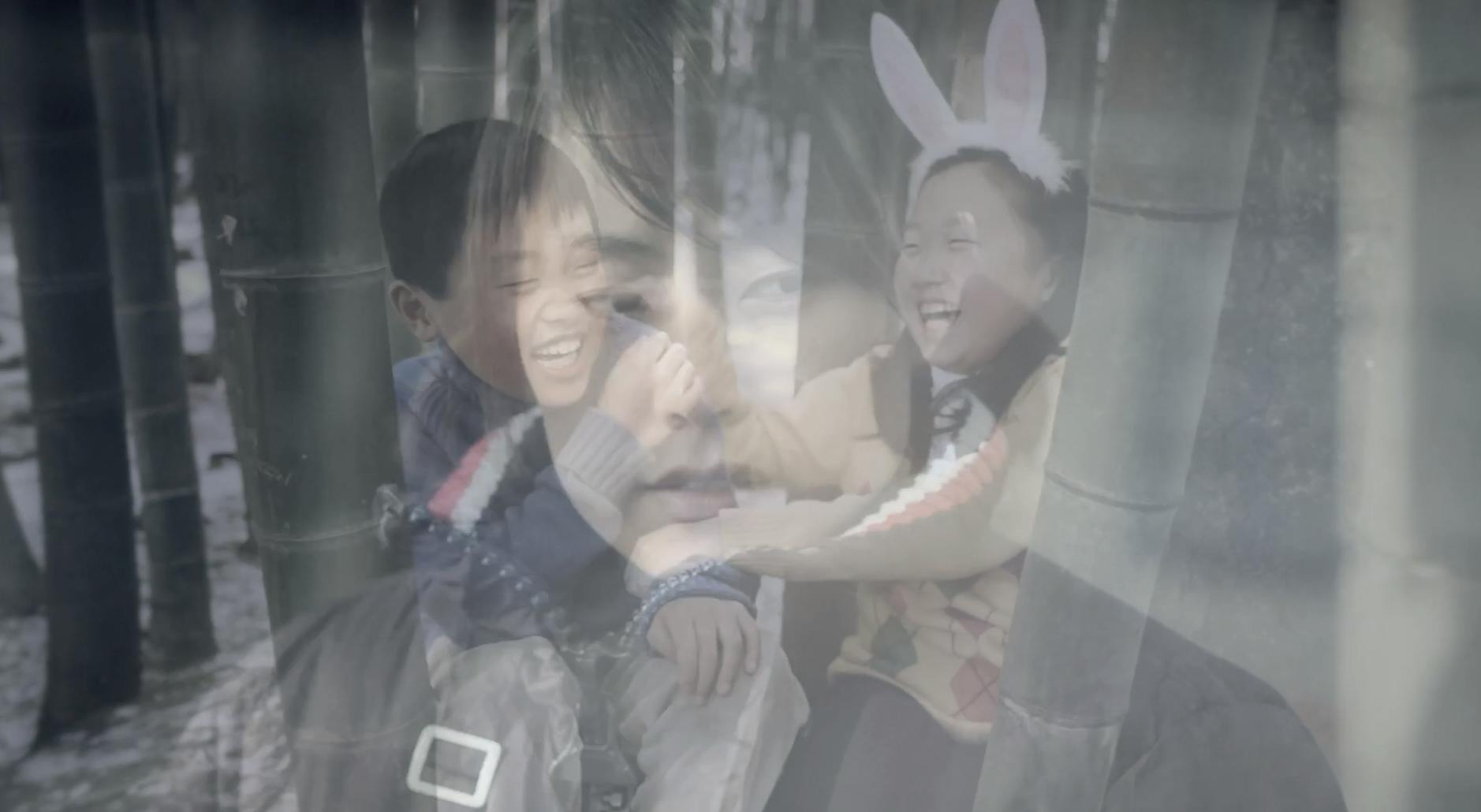

I believe in a way it is a mixture of attachment and detachment, which supports my vision as a filmmaker. The Sewol tragedy in ‘Last Letters” has been, and still is, a huge issue here in Korea. Due to frustrations with the Korean government over its crisis management, many families feel abandoned and even betrayed and a big part of the nation got emotionally very attached. In conjunction with the protest events, broadcast media and also local documentary filmmakers have started to cover the aftermath of the accident in order to potentially reveal what really happened and to speak out about the government’s reaction. This is important work, but maybe as one who culturally maneuvers in the middle ground I was able to look at it from a more detached angle, to do something unlike anything that had been done before and that is more in line with my previous work in relation to space and architecture. I also preferred to do something that addresses the issues of loss and memory in a way that the film could also be positive and help to give some degree of closure to the participants.

If you strip down “Bikini Words” it talks about a very sad subject matter and a dark part of Korean history. While conceptualizing that context, I also wanted to bring a certain lightness through humorous elements into the film, which in a way makes the subject matter more easy to digest and more understandable to a non Korean audience not familiar with the context and circumstances of the Korean military dictatorship at that time. In the end I feel that the films you make are a product of who you are. After living in Korea for 13 years, I make films as a German-Korean hybrid. Those are films that mainly identify with the underdog rather than the person who is always in the spotlight. Rather than portraying Korea as a dynamic, modern but also traditional heaven in Asia, I want my films to fill some of the gaps in a marketing machine of stereotypes. This is where I hope Korean and non-Korean residents find some value in my stories. Even though my films might lack the glamour and shiny facades of contemporary Korean pop culture, hopefully they map Korea as a more accurate and realistic place.

One of the unifying threads of this trilogy is the exploration of space, and a fascinating and intimate look at where people’s lives unfold. Is this something you think is overlooked in film or in our considerations of our own lives? Were the (human) subjects of these films aware of the mark they left in physical spaces or was this something they learned as part of the process?

My interest in space and architecture actually derives from the films of Wong Kar-wai. I graduated at Humboldt University in Berlin writing my master thesis on “space and architecture in Wong Kar-wai’s Happy Together”. Within my thesis I explained how Wong Kar-wai stages space and architecture in order to implement subtle messages about the identity issues of the people in Hong Kong before the handover to China in 1997. Back then during my research I came across a range of filmmakers who implement space and architecture related notions to their work, which vary a great deal in their approaches and intentions. Whereas Wong Kar-wai shows a lot of tight and congested spaces, directors like Michelangelo Antonioni or Andrei Tarkovsky show a lot of very wide and empty spaces and link them to a very poetic type of storytelling.

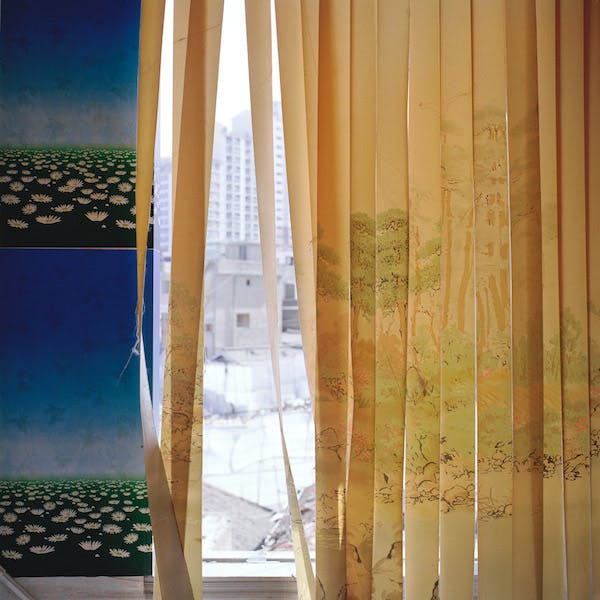

Based on this background during the years I have lived in Korea, I have mainly addressed issues related to space within my photography and film work. Some earlier projects talk about spaces of disappearance, others look at how urban and rural space are intertwined. Whereas some of my older projects were mainly inspired by raw concepts of urban development, each film within the trilogy was rather inspired by an event or a situation with a strong human focus, which made me take a more narrative rather than a strictly conceptual space related approach. Therefore this trilogy has altered my understanding mainly from a human perspective. But ironically most spaces within the trilogy are portrayed (mostly) as empty and abandoned by itself. The emphasis though is on the point of view of the camera. As the camera is floating, it feels like the audience is walked through the spaces of the trilogy. This way the audience in “Bikini Words” is taken on an imaginary trip back in time and gets an idea of the living and working conditions of the factory workers during Korea’s industrial period of the 1970s and 1980s. In “Last Letters” we see a very intimate picture of private space. The camera floats through the spaces which relate to the victims of the Sewol tragedy and their families. As we enter their homes, the audience is not only very closely connected to the victims of the tragedy, but in a way it is also reminiscent of Wim Wender’s film “Wings of Desire”, where the mobile camera embodies the point of view of the guardian angels, who are placed on Earth to look after the human beings. And last the strong correlation between the plastic mannequins and the spaces they inhabit, illustrate a sexualization of public space in “Plastic Girls”.

In terms of our considerations and in terms of our own lives, I think the trilogy illustrates that the influence of our environment on us and our way of thinking and behaviors is strongly linked. There is a lot of research that space and architecture has a strong potential to shape us as human beings into any direction. Whereas the environments of the factory workers in “Bikini Words” are a synonym of their harsh living conditions, the empty rooms of the lost ones in “Last Letters” directly link the deep grief felt by the relatives with the rooms after the tragedy occurred. “Plastic Girls” illustrates how easily our view on space can be manipulated, but also how we are responsible for ourselves, which decisions we make in our interaction with public space.

Plastic Girls is unique in this group in that it offers a judgment about sexualization of public space, and moves beyond the role of observer in the other two. Why this shift?

It is an interesting question based on a great observation, but the shift has been rather unintentional I have to admit. The trilogy was more a work in progress then a strictly conceptualized plan to start with. After the completion of “Bikini Words” my friend and business partner Neil Dowling encouraged me to follow up the film with two possible additional pieces. Based on the concept of the first film he saw a lot of potential in the trilogy. It did not take long to convince me, since I was very interested to see how this raw concept of space and architecture would unfold within a different narrative structure. Once I locked down each topic, I tried to not be too restrictive in terms of the aspects of storytelling, since each film was already embedded into a very rigid visual theme of the camera floating through the spaces of each film. I think what differs in “Plastic Girls” is that a larger truth is highlighted by the use of a thought provoking male gaze shown in the filmic non-architectural compositions, which in this case features the plastic mannequins. With more narrow focal lengths the camera is very close on the objects. The controlled, more or less fixed, handheld style makes us stare at various (private) body parts of the mannequins. Whether we identify with the gaze or not, it makes us feel very uncomfortable staring at the plastic mannequins and that reflects the relationship between the objects and the passersby who encounter them every day on the streets. I felt that since the mannequins aren’t real humans, it allowed me to take this approach without being offensive. I want the audience to understand that Plastic Girls is not a stereotypical display of female body parts but that it illustrates how the male gaze is supposed to interact with those plastic mannequins in a public space simply for the sake of commerce.

Were there any “runner up” ideas you had, ideas and interests about Korean culture you wanted to explore for this series which ultimately weren’t selected to be the subject of a film?

Once I have a new idea for a film it goes into a pool of ideas and mostly time proves whether this idea is able to swim by itself or whether is it is destined to drown. One idea I was really keen to use as the second installment of the trilogy, was connected to an older lady who was living in my neighborhood in Seoul back then. I originally met her at a bank. The bank I am talking about uses green as the main color for all their corporate and interior design. Since the lady was dressed in the same green color from top to bottom she really stuck out. I went up to talk to her and asked her if she had been hired by the bank. After that I kept running into her in my neighbourhood and it turned out that she actually dresses a different color from top to bottom each day she leaves the house. To me she seemed like a conceptual artist. At the same time she was also a local supplier of something which in Korean is called Neureungji. This is a food, which utilises the cooked rice, which burns to the bottom of the pot. After being dried, it is sold and then cooked as a rice soup. During times in Korea when people had little to eat, no food was put to waste and this type of food was particularly eaten by the poor. What is interesting about her is that despite her glamorous outer appearance she also did not have much and lived a very simple life. The neighborhood we were living in was a neighborhood which was facing re-development. As a consequence old housing had to make way for modern apartment high-rises. Due to this, entire neighborhoods would get demolished and rebuilt (something I talked about in my photo series Zugzwang before). In the end I ended up moving with my family, whereas she moved to one of the adjoining neighborhoods, which actually faces the same dilemma within the next couple of years.

In terms of a film for the trilogy, I thought it could have been interesting to have the camera float through small alleys of our neighborhood for the documentary parts of the film. The part with her, I envisioned to be a kind of fashion-film like layer in the film. Unfortunately I was not able to convince her to do the film. I tried really hard, but it felt like she did not want to be in the spotlight (even though this is exactly what she does every day), but then also she was dealing with a lot of health related issues, which made it hard for her to commit to something, which seemed to be really difficult and complicated in her eyes. So eventually I gave up, as I felt I had to move on with the trilogy.

At a later stage, I talked to my friend Sunmin about this old lady and she really encouraged me to try again to make this film. We decided to meet her for lunch in one of the local noodle restaurants, which she regularly frequents. It was pleasant to see her again and Sunmin really connected with her so well. When I told the lady that I was moving away from that neighborhood soon, she suddenly felt the urge to do it. She did not want me to leave the neighborhood without us doing the film. Nevertheless the trilogy was already finished. In a way that was good, since I really needed to simplify the concept due to her health conditions. She was struggling to stand on her legs for more than 1/2 hour a day. After all I shot with her for 10 days in 10 different outfits. It was just me and my camera, sometimes Sunmin would come along and our friend Rico joined if the shoot required help with sound. I plan to finish the edit of this film by the end of this year.

Can you tell us about Contented? How does working with a collective compare to working on your own?

CONTENTED is a company which I co-founded with my good friend and working partner Neil Dowling almost a decade ago. When Neil moved to Korea he was looking for a DoP to collaborate with him on his debut feature film called “Finding Joy”. We worked together very closely on this film and due to it being an independent production, it was executed among a small circle of friends. After the film Neil and I worked together successfully on a couple of music video competitions. The video we made for the Norwegian band Röyksopp for their song “Senior Living” was selected for the prestigious Saatchi & Saatchi’s New Directors’ Showcase at Cannes in 2011 and received a nomination at the UK Music Video Awards the same year. With all that CONTENTED, which at first was only a label for an independent production of a feature film, became something more solid and more and more it transformed into a production company, as we went along and took on bigger commercial jobs. Today we are pleased to have collaborated with a number of high profile clients like AirBnB, Burberry, Facebook, Google, Cheil, Chevrolet, Hyundai, Millet, GS Caltex, Hanwha, Pepsi, Samsung, MTV, Nike, Starbucks, Western Union. Since we have been based in Seoul for over a decade, but also work in most parts of Asia, I think what makes us strong is that we are familiar with, and sensitive to, Asian cultural norms whilst also being able to incorporate our European perspective and sensibility.

Thinking back CONTENTED really fell into place organically. Foremost it is a platform for all our commercial work, but then it is also meant to be a supportive platform if either Neil or I, or anyone within the network, wants to work on a personal project. The Korea related trilogy was such a project. Even though it is merely a personal project, CONTENTED was the foundation of the films and provided the infrastructure to execute each project. Even with those kind of personal projects, we tend to communicate a lot and try to help and support. In the end each personal project is also a team effort. Films are never done alone. Fortunately we can always rely on the people who we work with, but we also try not to exchange staff on a regular basis. We try to stick together and learn from each other’s and our own mistakes. This is how we feel we grow and this is why each of us has a huge influence on the work we produce. Our producer Kuiock Park for example had a huge positive influence on most of our projects until she left to pursue her dream of becoming a screen writer. Now our new head of production Mini Kim is a very strong driving force, who helps us to realize our concepts. In the camera department we worked together with our close friend Sungil Lee. Most of our music and sound mixes are executed by Udo Lee, who adds a very personal touch with his composing skills. As a graphic designer In-ah Shin has worked with us on many projects. Her most outstanding work is probably her thoughtful design for “Plastic Girls”. We hope that everyone who works with us takes pride in the work we do with CONTENTED. We feel that everyone also has a lot of creative freedom, once they prove that they are good with what they do. The fact that all the people in our network are mostly our close friends, makes it fun for us to take on projects and collaborate together from start to finish. In a way to us CONTENTED is family – maybe this is the reason why everyone is always ready to give their best.

Your film style is refined, it must have changed over the years. If you could somehow speak to novice Nils at the beginning, what would you tell him?

This is a tricky question. Probably it might be best to tell a novice Nils not too much, since it is the ups and downs you experience, which I feel really shape you as a person and connected to your work. One’s personal and creative journey is something which is also hard to predict, and it is also something you cannot really plan around. During some of my downs I had initially thought of quitting filmmaking – especially during the time I spent in film school. Even though they were also very valuable experiences. I recall that back then I often felt frustrated to see professors trying to shape your work very one-dimensionally without having any understanding that what you do is so much linked to who you are. For example, my second and my third short films have both been linked to very personal experiences. Both films have not been easy for me to execute and now with a distance of course I see their weaknesses and don’t consider them as mature work. But when my professor devalued the films as too narcissistic, I was kind of offended and made the decision to not further engage myself in personal stories connected to my own life only to be on the safe side in order not to fail. Fortunately I happened to have a strong interest in architecture and urban space, which at that time culminated in my master thesis on space and architecture in Wong Kar-wai’s Happy Together. That sort of gave me a vision and a path to follow as a filmmaker. But still sometimes I wonder what kind of films I would be making now, if I would not have followed that direction of interest. So probably if I can make a suggestion to novice Nils, I would tell him that he should always follow his instincts and not get bogged down in too many insecurities, and be confident about the stories he wants to tell.

Even though I also direct, I don’t see myself as a director per se. I am merely a visual person and consider myself first of all as a cinematographer. I kind of started to direct out of necessity. My fellow directing students at film school, I felt did not take their role too seriously. Rather than putting together a decent script, they wasted a lot of their time following online news about which new camera has been just released. It was that time where a new camera hit the market every other month. After getting tired of shooting mediocre scripts as a cinematography student for my fellow directing students, I felt that I could do a better job myself. This is how I started to direct and edit myself. After all to be able to play multiple roles I find really liberating. Interestingly this happened at times where the traditional filmmaking system got stirred up due to the rapid developments in technology and people within the industry were less assigned to the one role of their trade. As a filmmaker during these times, I think one needs to be more flexible than ever. Especially the job of a director lost a lot of its initial glory. These days everyone needs to be much more proactive and skillful in multiple tasks. These days more and more directors pick up the camera to shoot or they edit themselves instead of simply telling an editor what to do. So based on this I would probably tell novice Nils that skills and know-how are key and that despite the need to specialize in something, one also has to widen their horizons in different fields of filmmaking with a very open mind and positive attitude.

I am honored to hear that my work is seen as something which is “refined”. I think in this regard novice Nils should understand that something refined is strongly linked to one’s personal interests and connections. Let’s face it, there is so much great content available these days. Therefore it is easy for us to get carried away and try to imitate what renders success. So hopefully novice Nils will understand that it is important to be inspired, but in order to tell a successful story, it is important to stay true to ourselves and our ideas instead of trying to reproduce what others have already done before.

You can keep up with Nils and see his new work on his Website

Plastic Girls, Last Letters, and Bikini Words can all be found on his Vimeo

Also check out his work with partners on CONTENTED

Interview by: Ryan Ernst

Portrait by: Max Reed