Dialogues Two: Corporate Patronage in the Arts

In the United States, funding for the arts has become a notoriously difficult endeavor. The already underfunded National Endowment for the Arts just narrowly escaped extinction.

And artists and galleries continue to struggle in a stagnant market. Is corporate patronage the answer? In April, we sat down and chatted about the potential advantages, and challenges, that corporate funding can create.

And artists and galleries continue to struggle in a stagnant market. Is corporate patronage the answer? In April, we sat down and chatted about the potential advantages, and challenges, that corporate funding can create.

Christine, Troy, Ben and Levi have joined the Dialogue.

Christine: Hi there!

Ben: Hello!

Troy: Hey everyone

Cool everyone’s here!

So to start this convo and help the audience, how are we defining patronage? What is patronage?

Ben: We typically use the word “patronage” to mean funding the arts or audacious creative endeavors. But I know you guys have done some research on other examples of patronage and how this meaning has changed over time.

So, What are some examples of patronage outside the art world?

CHRISTINE: I mean, I think it’s any situation where you enable something to happen without someone having to sell it…

TROY: Privileging someone else in a way, through financial means?

CHRISTINE: Yeah, supporting them in…

in religion, journalism, politics at times. You can even say, I guess, the donation by people–politicians receive donations, and science as well, with people donating to science in order to find a cure—can all be considered sort of patronizing certain people.

Christine: Yeah, supporting something that isn’t necessarily like– you’re not getting something [direct] in return for it. You’re just supporting it out of your own good will.

Troy: Merriam-Webster dictionary defines it as a role of superiority, which is interesting to think of the role as a power dynamic

Christine: The word “patronize”?

Troy: Yeah. Or even when someone says, “You’re patronizing me”…

Ben:

Troy: …it’s just interesting to think in that context. Not that they’re the same, but thinking about the patron fundamentally as the distributor of power.

Christine: I also googled “define: patron,” and the term relates to the patrician-client relationship of Ancient Rome. A patrician, I guess, is the former owner of and protector of a freed slave. “Clients” were former slaves that were freed by their “patrons,” and then received benefits like financial loans, legal help, and other things.

Troy: Such a strange Wikipedia search, but provides an interesting historical context for the term.

...it's interesting to think in that context. Not that they're the same, but thinking about the patron fundamentally as the distributor of power.

So with that knowledge, how has patronage shaped the art world? I think most people would consider patronage and the art world very closely tied together. I have a feeling it’s been seen a lot in history and that’s why we have that connotation. But what’s the history that’s shaped how we’ve gotten to where we are now?

Ben: One of the oldest examples of patrons I know would be the Medici family. They were a very wealthy Florentine banker family during the renaissance who funded works by Michelangelo, Raphael, Brunelleschi. They also controlled the Catholic church since they had 4 popes within the family. They used their art patronage as well as the selling of indulgences to fund a powerful and enticing image of the Catholic church.

Ben: Eventually people became frustrated with the church’s extravagance, feeling that it was distracting from the true meaning of religion. It was this backlash that sparked the beginnings of the Protestant Reformation. To be fair much of this backlash was over the selling of indulgences but those indulgences went to fund lavish works of art. This example shows the tenuous relationship between artists, patrons, institutions, and the public as well as how long this debate has been alive.

And what’s happened recently in the ’80s, ’90s, or even 2000s?

Ben: There’s been a lot of changes happening in public policy in regards to the patronage of the arts, with the Arts Council in Great Britain, or the NEA in the US. And this has prompted a lot more corporate sponsorship. It’s becoming increasingly common for banks, vodka, energy drinks etc. to be involved in a new form of patronage. Art and advertising are beginning to blur and the distinctions of public and private are becoming less clear.

Christine: And part of this change in policy of the Arts Council and NEA… is that because of a lack of funding, that they’ve reduced their budgets for the arts?

Ben: Definitely, the NEA’s budget was cut in half in 1989. A lot of this pressure to cut the NEA began in the 80s when artworks like Andres Serrano’s Piss Christ, and an exhibition by Robert Mapplethorpe got caught in the fray. They were used as examples to illustrate what some politicians deemed as “inappropriate” misuses of public funds while others recognized that censorship was at play. This resulted in protests against measures to defund the NEA. The NEA is still around… for now. However, these tensions are still strong, resulting in less and less public funding for the arts today.

Christine: Less government funding for the arts, means more funding that needs to come from elsewhere. Naturally, this leads to an expansion of how we imagine this patron relationship. Who or what do we imagine to be patrons? Who should they serve?

I would even kind of bundle in the collaborations that some brands are doing with cultural figures, artists, musicians, etc—patronizing them to, essentially, help create a product; or use their image or message in collaboration with their brand in order to express a certain feeling or idea. But it’s a very loose definition and connection. I think there’s more interesting ones happening recently. So what are some corporate patronage going on in the art world now? How are things changing?

Christine: Well, we’re seeing some examples of corporations that are trying to support artists, but take more of a backseat and give themselves…give them freedom that they wouldn’t have by themselves in the art market. One example is maybe Red Bull: they’re trying this really hands off approach to really support artists and support emerging artists, and provide them a space to show things and funding. But also not have the Red Bull logo and the brand be that much a part of it. So I think that’s a new thing, maybe? Where we’re seeing the corporation totally step back.

Troy: It’s true, they are stepping back, but only so far *takes sip from Red Bull can*…It really depends on each brand. At the end of they day, they are still trying to push a product onto their audience.

Is it more like they are providing an “open canvas,” exhibition space, whatever, for the artist to do whatever they want?

Troy: I guess…it depends…

There’s been a lot of discussion around defunding the National Endowment of the Arts, which I think is playing a major role in why art patrons are becoming more prevalent, and why more corporations in particular, are hopping on the art wagon. We are starting to see a greater public conversation around the lack of government funding towards the arts in the US. Look at the response we got from Artifax, 4,000+ faxes sent to congress about why the NEA needs to be protected. From a local to a national scale, arts funding has been hurting.

We are starting to see a greater public conversation around the lack of government funding towards the arts in the US. Look at the response we got from Artifax, 4,000+ faxes sent to congress about why the NEA needs to be protected.

The gallery scene here in early 2017 isn’t looking great, especially the galleries that are funding young artists. So, corporations, either accidentally or seizing an opportunity, have a chance to support the arts and young artists. Possibly including a branding affiliation in order for both of them to succeed in this market right now.

Christine: And that’s a shift from the 80s when a lot of corporations were supporting more established artists.

Yes, and museums putting a logo on a gallery show was much more common. That was what a lot of corporations would do in order to feel good about themselves, but also help artists out. This was one of the variety of ways to sell their products.

Troy: There’s also cultural capital, which feels gross to say, but some campaigns can’t capture a cultural ethos in 30 or 60 seconds. So in a way, commissioning artists provides corporations a vessel directly into culture, into contemporary topics and into art history.

Good point! I know back in the ’80s patrons were banks and oil companies like Wells Fargo and Exxon Mobil, but what are some of the other examples when we say corporate patronage?

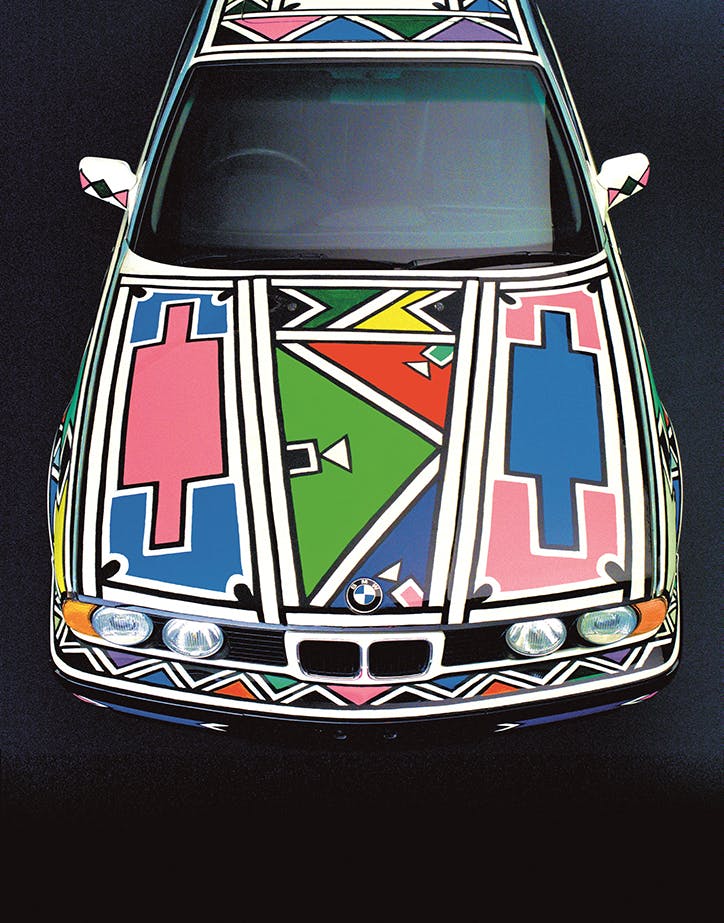

Ben: The BMW Art Car has been around for a while. Actually, do you guys know how long it’s been going on? [starts googling] According to Wikipedia, it’s been around since 1975. The first one was Alexander Calder, Roy Lichtenstein, Robert Rauschenberg in the 80s, Esther Mahlangu in the early1990s. I love her design, it’s beautiful!

Ben: They’ve worked with a bunch of excellent artists. Jenny Holzer, John Baldessari…

Christine: Jeff Koons.

Ben: Oh yeah Jeff Koons! So many great artists.

Ben: Most of our examples still seem to be big established brands or luxury brands, large banks, oil companies working with established artists. These seem to have been more common in the past. But now smaller, younger brands are becoming patrons of the arts. Like Red Bull.

So let’s talk about Red Bull Art really fast. What have you seen them do as a corporate patronage that’s interesting or different than maybe what a bank like Wells Fargo has done?

Ben: Well, I think there’s been a lull in the art market, especially with mid-level galleries trying to keep their doors open or give a platform to emerging artists. That’s really difficult so they’re looking to other people to work with, other brands to work with. Red Bull has sort of stepped in and are working with a lot of up and coming, very contemporary artists and musicians through their program. Very different from the old model of patronage.

We also are fortunate enough to work with Google Arts and Culture. Our work with them ties closely to Google’s overall mission and values, supporting projects to realize and document artists, so a little bit different than some of our other clients such as Bohen. What do you see the two differences being in both the work that we’ve done for Google versus the one we’re doing for the Bohen Foundation?

Troy: The Bohen Foundation is a great example of an art patron that doesn’t have an ulterior motive. They aren’t pushing their own product. They are genuinely supporting contemporary visual culture—helping make it happen. Commissioning art to be made for the sake of the artist’s career. They find the artists that they want to work alongside, amongst, within their practice, and distribute their works through donations to museums. From what I’ve gathered, looking at Bohen’s history, it’s more of an organic process. Where Google Cultural Institute has to abide by a corporate mission: “to organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful.” They have to cater to their own product. I guess that’s the biggest difference, a corporate mission versus an independent mission.

Christine: Yeah. And I would say that those different missions have led to different kinds of documentation, that we’ve worked with, in making websites for them. For example, I think Bohen Foundation has been so in the background in what they’re doing and has been so invested in supporting artists that they don’t have as much documentation of their own projects as maybe Google Cultural Institute does, because their main mission is to document and organize. And also it’s important that they become a visible entity so they can visibly reflect well on Google the company, as a whole. So I think that those different approaches translate differently onto the web because they have different sorts of ways of recording what they do. And so then translating that into a website presents different challenges and different opportunities because they’ve maybe spent less time documenting what they do.

I guess that's the biggest difference, a corporate mission versus an independent mission.

Troy: Totally—it was interesting to see Bohen’s documentation, some of their older videos are like 200 by 100 pixels in dimension, lol— which is so small. Figuring out how to make the lower resolution work next to the higher resolution image. I appreciated the earnest nature of it all—the results look super cool. There’s something authentic about it—incongruous artifacts in documentation.

Christine: Yeah. I think Google—especially if you look at the SPAN events—I think that’s their effort to try to contribute strongly to design and technology, culture, and discourse; and try to provide a platform to things rather than just put their name on it, be a real channel for things.

Ben: Yeah, definitely more tech focused or at least interested in how technology frames the work.

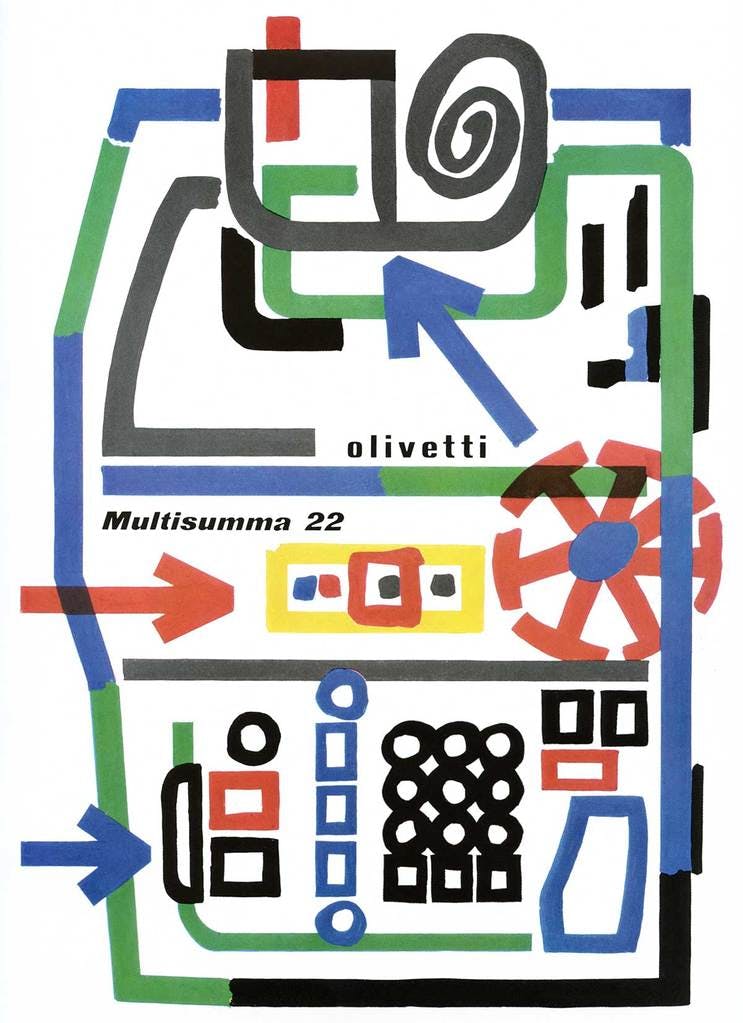

Christine: And I think they also model themselves a lot after Olivetti, which was a typewriter company from the early to mid 20th century. And Olivetti was a huge sponsor of a lot of artworks that worked with technology. And because those technologies required a lot of design, research, and support, it became a really symbiotic kind of collaboration between the artists and that company. And that became actually a really fruitful patronage scenario because those artists actually couldn’t really make those works without the technical support from Olivetti as well. They didn’t really have as warm of a reception within the more formal art world because their artwork was a little bit unconventional and a little taboo. So I think that we’re entering an exciting time, in terms of patronage for technology-based artworks. And Google’s kind of navigating that and trying to figure that out in some progressive ways, hopefully.

I think that we're entering an exciting time, in terms of patronage for technology-based artworks. And Google's kind of navigating that and trying to figure that out in some progressive ways, hopefully.

Ben: Definitely. Google has been doing a really good job with that lately. Especially, with Rob Giampetro as head of design now.

Christine: Yeah.

Ben: He has an excellent understanding of the responsibility that comes with curating culture as well as how to document and design with cultural institutions from his history at Projects Projects. I was disappointed when he left Projects Projects but I’ve since changed my mind. I’m much more optimistic now about him bringing his sensibility and nuance to the reach and capital that is Google. And like you said Christine, the SPAN events have been great for bringing much needed critical discourse and cultural sensitivity to the tech community.

Christine: Totally. With great resources, you can help to spread information and educate people about new technologies and the possibilities that they can bring. And I think that that’s a kind of support that’s hard to get outside of corporate scenarios sometimes when it comes to educating about the cultural possibilities of technology.

So it seems like the biggest shift that’s happened in the last 10, 15 years with corporations as patrons can be distilled down to getting out of the way. They’re being hands-off with their supporting artists―you could even lump designers, architects, others in this space. Letting them do what they do best, from Red Bull, to Google Arts & Culture, to Tiffany’s, giving them a platform with no restrictions and hopefully, no stipulations about what they have to do or can do. Less of a dialogue and more of a platform at the end of the day, which is exciting, especially if funding for the arts is evaporating in certain circles or certain areas. I guess the biggest question then is, what are some of the ramifications of this new corporate and art relationship? What are you see seeing that scares you or could be an issue if we’re talking about this new relationship that’s developing?

Ben: At first glance I was hopeful for this new dynamic between artist and patron. However, upon more analysis I have a lot of concerns. This more informal relationship hides this power dynamic behind patronage and blurs the line between art and advertising. I remember we were just brainstorming earlier about artists who are working with brands and Kanye came up. I think Kanye is a talented musician, but in many ways, he has become as much of a brand as an artist. This blurring is worrisome to me. I don’t think a lot of the public knows how deep brands go to hide their influence on the public. One thing I recently became much more aware of is the buying of influencers. I think there needs to be more awareness by artists and consumers of culture of this power structure in which we are all participating.

Christine: Right. Maybe certain artists want to make sure that they don’t become brands themselves, and maybe it becomes difficult to operate that way and not compromise oneself, but also attract sponsorship money.

Troy: I think it also sets up a predicament in some ways, where a corporation has a product and agenda, and an artist has their own art practice. How does one acknowledge their own voice and art practice in relationship to the corporate product? Will the corporation leave room for self critique and self improvement? Does the relationship between corporate patron and artist just become a slick PR campaign? I think that’s important to tease apart. I see potential conflicts in an artist’s subject matter conflicting with the systems and structures behind the brand of the corporation. Combining two different worlds that are actually opposing each other, but on the surface look cool and relevant.

Christine: Right, the context could compromise your artwork, so this new condition of more corporations stepping in requires maybe more vigilance from artists to really research where the money comes from. So, it’s a question, as well, what’s the pressure on corporations to make sure that they’re held accountable and how do we have transparency around how they work or whether they’re a good source of money.

Ben: Yeah. As this practice is becoming more common, instead of denying this reality, I think we can try and proceed forward in a way that’s more conscientious and thoughtful. And I know, Troy, you have some excellent ideas about how to more responsibly navigate this new world of patronage.

How does one acknowledge their own voice and art practice in relationship to the corporate product? Will the corporation leave room for self critique and self improvement? Does the relationship between corporate patron and artist just become a slick PR campaign?

Troy: Yeah. I personally feel like there needs to be some kind of governing body that can think about these relationships without a bias that a corporation would have. A governing body that could oversee these relationships, set some parameters for what it means to be a corporate patron—dare I say….vetting corporate patronage? And maybe there’s not only one, but several certified intermediaries. That could help protect artists right off the bat: “Do I align with this product? Is this something I want to associate with?” and same for corporations. That’s one way to compensate for these dicey situations.

Ben: Definitely. I think it can be mutually beneficial for both parties, increasing the cultural capital that these corporations gain, but also maintaining the integrity of the work of the artist.

Christine: I also think one way that could help us—kind of piggybacking off of that—was proposed in this New York Times article from the ’80s. And it was talking about how maybe it’s better if a corporation donates to a pool of money versus funding a specific artist or exhibition because, then, the curators or the artist doesn’t have to think about how best to match what they have with the corporation. And the corporation doesn’t have the chance to influence those situations. Then the curator or the artist can just draw from a general pool of money and still make independent decisions. And that’s kind of what happens, anyways, if a corporation just generally donates to a museum or something, or institution. So that’s a sort of half way of having that governing body oversee the money and limit corporate influence. So it’s still helpful, but it’s not changing the kind of art that people see.

I think it can be mutually beneficial for both parties, increasing the cultural capital that these corporations gain, but also maintaining the integrity of the work of the artist.

It’ll be interesting over the next few years, especially with Trump in office, to see where the arts, and corporations, end up and how those two play together—especially with recent threats to cut the NEA. Where is funding coming from? Where is arts education coming from? Is it going to be supplied by more corporations as they enter that field? Is it going to be more grass roots? I think, right now, the trend is happening in both areas, but moving forward it’ll be interesting to keep our eyes on.

Troy: Definitely.

Ben: Interesting indeed.

Christine: Until next time.

Christine, Troy, Ben and Levi have left the Dialogue.

Here are a few of the essays and articles that inspired our discussion:

Illustration/ Animation by Justin Kielbasa & Troy Curtis Kreiner