The Philosophy of Advertising: Strategist Faris Yakob Talks Shop with Use All Five

Let’s start with the name Genius Steals. What’s the origin and meaning behind this name? Why is it significant to you? As someone whose professional motto is “be nice”, how can we understand the word “steal” in this context?

The phrase “talent imitates, genius steals” is usually attributed to Picasso – as Banksy does, as Steve Jobs did in interviews.

Actually, it’s what I call a fauxtation, a quotation that just manifests in culture in a certain form and then gets appended to whichever famous person seems most apposite, like Mark Twain, Picasso, Einstein or Oscar Wilde. I’ve been using the quote as the name of my blog since 2006 but I started playing with it way back at University.

The closest actual referent, which is where this version evolved from, is by T.S Eliot, in a piece of literary criticism he wrote, trying to explain how one could judge a creative work — how one could establish a criterion of judgement beyond subjective response, which renders every opinion equal. It’s brilliant:

“One of the surest of tests is the way in which a poet borrows. Immature poets imitate; mature poets steal; bad poets deface what they take, and good poets make it into something better, or at least something different. The good poet welds his theft into a whole of feeling which is unique, utterly different from that from which it was torn; the bad poet throws it into something which has no cohesion. A good poet will usually borrow from authors remote in time, or alien in language, or diverse in interest.”

Anyone who has ever worked on anything involving creativity, with words or pictures or numbers or science or technology, eventually comes upon the idea that “ideas are new combinations” to quote James Webb Young, that “nothing can come of nothing” to quote Shakespeare, who was quoting Lucretius, who was paraphrasing Parmenides. See what I mean? That’s why I say originality is a myth.

All culture is accretive, made of increasingly complex networks of strands of itself. I have a terrible memory for things I’ve done and people I’ve met, but my brain loves to dredge up random facts and quotes to apply to situations and problems. It’s that observation about how my brain works that led me to the quote.

The point is to demystify the process of creativity, which is something that I’ve noticed insecure creatives really don’t like, but that secure ones take as entirely obvious. It’s just a process of combining pieces of inspiration in service of solving a problem. The more interesting things you put onto your tabula rasa, if you will, the more legos you store to build ideas with. One cannot invent without inventory.

This is not copying, copying is lame, although of course when we are learning, we copy. Then we attempt to build on it. Copying tries to disguise the source, whereas stealing is taking the whole piece as allusion and using it, references and all.

Stealing multiplies meaning, whereas copying reduces meaning to hide its debt. Copying is a forgery, stealing grabs the whole thing and smashes it into other things to create new things. It is nice because it acknowledges and builds on what came before. All art is a comment on all prior art.

You have described yourself as an advertising philosopher. Why use this word in an industry that is obsessed with data? How does the trend of aggregation and analysis of massive amounts of data affect your work?

It started out as an insult, a gentle one, but an insult nonetheless.

In the dark underbelly of the comments, vitriol is snowballed back and forth among anonymous trolls and in this space someone accused me of being a philosopher.

They were implying my concerns were abstract and highfalutin, not grounded in the here and now of making stuff. I found this enlightening in several ways. There is a strong vein of anti-intellectualism in America. Richard Hofstadter won a Pulitzer Prize in 1964 for his book, Anti-Intellectualism In American Life, about how it underpins political life, with climate deniers and creationists two obvious current examples of the rejection of science.

Issac Asimov wrote ”There is a cult of ignorance in the United States, and there has always been. The strain of anti-intellectualism has been a constant thread winding its way through our political and cultural life, nurtured by the false notion that democracy means that my ignorance is just as good as your knowledge.”

I think he nails one of the most important points here, the conflation of strongly held opinions with truth. The comment also made me realize that we don’t have a philosophy of advertising.

We simply do not have a robust model for understanding how symbols dispersed through media create non-obvious economic effects. All the evidence is blurry, no doubt in part because it can work in so many different ways. I look at this in detail in my book. Philosophy is studying the theoretical basis for the praxis as it builds on fundamental principles. It is, like all thinking, built from observation and reflection – i.e. data and analysis.

Without a robust model for how something works, how can we be confident that it will? Even more importantly, how can we possibly make it work better? And this began to make sense of another countervailing notion in the advertising discourse, that we had to stop over-thinking and “get excited and make things”. Nothing wrong with making things of course, but I realized this is the ultimate defeat of strategy, the belief that nothing can be given a better chance of success through insightful analysis and thought, and so we should just throw things against the wall and see what sticks. For a business in the business of helping other companies make more money, that just doesn’t make sense.

I do believe that in a complex world it’s impossible to predict what will work, especially as it impacts culture and human behavior. But that’s not the same thing as saying we shouldn’t try to give it the best chance based on learning and hypothesis. It’s like saying well I could get run over by a bus tomorrow, so there’s no point in watching my diet. You don’t know what will happen but you can increase your odds of a healthy life through your behavior.

Ultimately, in the shadow of ignorance, the most strongly held and vociferous opinions will win out. And this is what it was all about. Creatives and creative directors excel at having strong opinions in uncertain conditions – it’s part of their job. The uncertainty gives them the doubt they need to sell whatever they want to, to make “cool stuff” for their book or the award shows. I suspect this is why many of them seemed to reject the rigor of thought we were reaching for back then. Unfortunately the same uncertainty also leads to some of the least interesting work, where the most conservative common sense outweighs creative opinions.

It was in a conversation just last week with a very nice young creative on Twitter that this really landed for me. We were discussing a piece of work he didn’t like and I was suggesting some ways it might be effective. He ended the conversation by saying, “No clever research is going to convince me to doubt my gut feeling, I’m afraid.” and I was like AH! That’s the point, that’s the problem.

In your book Paid Attention, you tell us a lot about the history of advertising to help us understand where the industry is and where it’s going. Will this kind of historical analysis change as our culture accelerates? Will it get any harder to make predictions about the future in our new digital environment?

It’s hard to make predictions, especially about the future, as the physicist Niels Bohr famously said. (Except that he didn’t, it’s another fauxtation.) There are no simple answers because of the nature of complexity. Systems created by the interaction of lots of independent agents with partial information and their own objectives have emergent effects that are inherently unpredictable. (Like the weather.)

I have a theory that things have become more unpredictable because the latency of culture has diminished because of technology. That is to say, things are communicated through the system faster, creating effects, which in turn become causes (because it’s a closed system), faster and faster. So lots of loops are created with ever increasingly unpredictable effects. It’s only a theory, but my brother who has a PhD in mathematical modeling is working with me on models that seem to support it.

Regardless, history is all we’ve got. It’s the only live set of examples of things happening in the world we can learn from. So it makes sense to study it, with a reminder that of course that we can’t drive just by looking through the rear view mirror.

”Life can only be understood backwards; but it must be lived forwards.” – Soren Kierkegaard

Forbes and Wired, among many other online publications, recently walled their content to adblock users. What are your thoughts on this?

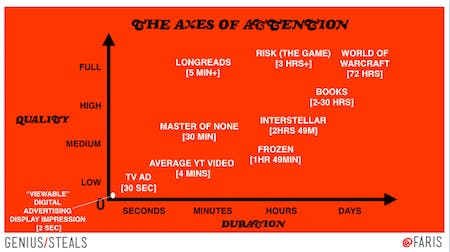

I’ve said very publicly that I think Forbes has had the most obnoxious digital advertising experience of any major business publication. It forces you to sit through these interstitials with these trite quotes, forcing you to pay for their content with that amount of attention. Then you find out that a lot content on Forbes is unpaid contributors writing self-promotional puff pieces pushing their own products or approaches.

In general I think this approach is incredibly shortsighted. The Forbes blocker is very broad, it blocks me even through I’m only blocking tracking using Ghostery, not the ads. It says “We noticed you still have ad blocker enabled. By turning it off or whitelisting Forbes.com, you can continue to our site and receive the Forbes ad-light experience.”

But if you do turn it off, as we found out in January, it actively served you malware as soon as you did. So that’s part of the problem. What Cory Doctorow has called the inherently toxic relationship between advertisers, publishers and readers has metastasized into the ad network and third party tracker adtech landscape, which leaves all of us open to these sort of security violations.

Everyone talks about how obnoxious the Forbes interstitials are. And without reputation, a business media entity is not really anything anymore. It was the environment, the stature of having your by-line there, that made people want to be in it.

With Wired, it’s in some ways even more of a betrayal since they invented the banner ad and their audience over indexes heavily towards blocking tracking for security reasons because they know the dangers better. It’s also because of the price they ask – $1 a week – may seem small but is several orders of magnitude higher than their average advertising revenue per user.

Ultimately, as Metallica found out, attacking your fans is never a good strategy.

Shane Smith, CEO of Vice, recently commented on the state of media agencies by saying, “We want to make great shit but it’s a war to do it every day because people don’t want to get out of their standard operating procedure.” Have you seen this struggle to adapt in agencies? How can industry leaders address being too risk averse?

I used to work at a media agency, and we worked with Vice on projects way back in 2004/5 when they were a tiny free counter culture magazine. I see both sides. Vice made a name for itself doing what other people wouldn’t do, so it’s somewhat disingenuous to say the industry’s conservatism is holding back our great ideas. That said, media agencies exist to buy media. They may do other stuff now, but trading is at the heart of the business model and trading requires fungibility, it requires currencies, it requires standardization. If media agencies had to create a new trading model, a new exchange medium, a new approach, for every single campaign or buy they would stop being profitable standalone entities.

Just as Vice wants to sell products that make them money, agencies want to sell the products they make that make them and their holding companies money. That’s why we were appointed to lead strategy when I worked at Naked for the roster agencies tasked with buying media and making ads and so on. If you ask a fishmonger what to have for dinner, they aren’t going to recommend steak. Of course the same is true with agency partners; they are biased by business mode and belief to recommend a type of solution.

But, I also refer you to the above answer around philosophy, because we should remember that the creative professional will always struggle against the whatever system to “make great shit”, that client organizations are even more conservative than agencies, and that our job is to make clients money, not “great shit”. Of course powerful content can be one way we leverage creativity to create value for our clients, but what matters is the effect we create, not the things we make.

We can all see the personal appeal of being a digital nomad, was there a professional appeal to starting Genius Steals?

As with many big decisions, there were inherent appeals and fears. The appeal of being independent is hard to overstate. I started to get very senior when I was at advertising agencies, and what you of course realize is that no matter how senior you get, you still have a boss, who has a boss, who has a boss, who has shareholders. You are never free if you work for someone else. Working for yourself is fundamentally different – you can do literally whatever you want – but it comes with huge risks, of not making any money. Salaries are there every month [until they aren’t] but that regularity comes with its own costs.

Beyond the business freedom, it also freed us up to do different kinds of work. For years while working in New York I would regularly get these emails where someone would ask for help thinking about a problem, or working with them on it, or asking about how they might think about problems in general. As a loyal agency person I tried to turn these vague requests for help into business for the agency but it very rarely worked. Unless the client wants to spend millions of dollars on advertising, it’s hard to make the economics of a NYC agency make sense – the overheads are just too high, there’s a factory that needs constant feeding.

An advertising agency simply cannot suggest taking the whole ad budget and using it elsewhere. Ultimately the agency advice has to push clients down an advertising pipe or it hurts the bottom line.

At Genius Steals we have very low overheads and we have no factory to feed – we work with a network of collaborators on projects as needed. So we can recommend whatever we think is best for our clients on lots of different kinds of projects and we can work with lots of kinds of agencies at the same time.

We’ve worked on NPD projects for P&G, brand strategy for Gibson Guitars, created content for Marriott Hotels, run consumer experience workshops for InterContinental and digital strategy workshops for Coca-Cola. We’ve worked with creative, media, digital, PR agencies and more, on their processes, as consultants on pitches or as part of a team on client projects.

Because we don’t have a factory to feed, we don’t need retainers. In fact, we refuse them – we only work on projects, from one hour keynotes and up to four month consulting and creative engagements, but nothing longer. This is another appeal for us – we get to keep learning, coming in fresh to the brand and the engagement each time while gaining experience across categories, geographies and disciplines.

Travel. Please tell us anything you want about travel.

It’s good for you. If you end up somewhere near us, let me know and I’ll buy you a drink.